Filipino Women Animate the Resistance

From 70s Chico River to 2026, Pitak Project

There’s a story almost every Filipino activist knows, and every Filipino should know. It’s a story of resistance, of remaining immovable in the face of violence. It’s a story of both loss and triumph—a guide for resisting today. And it’s also a story about breasts.

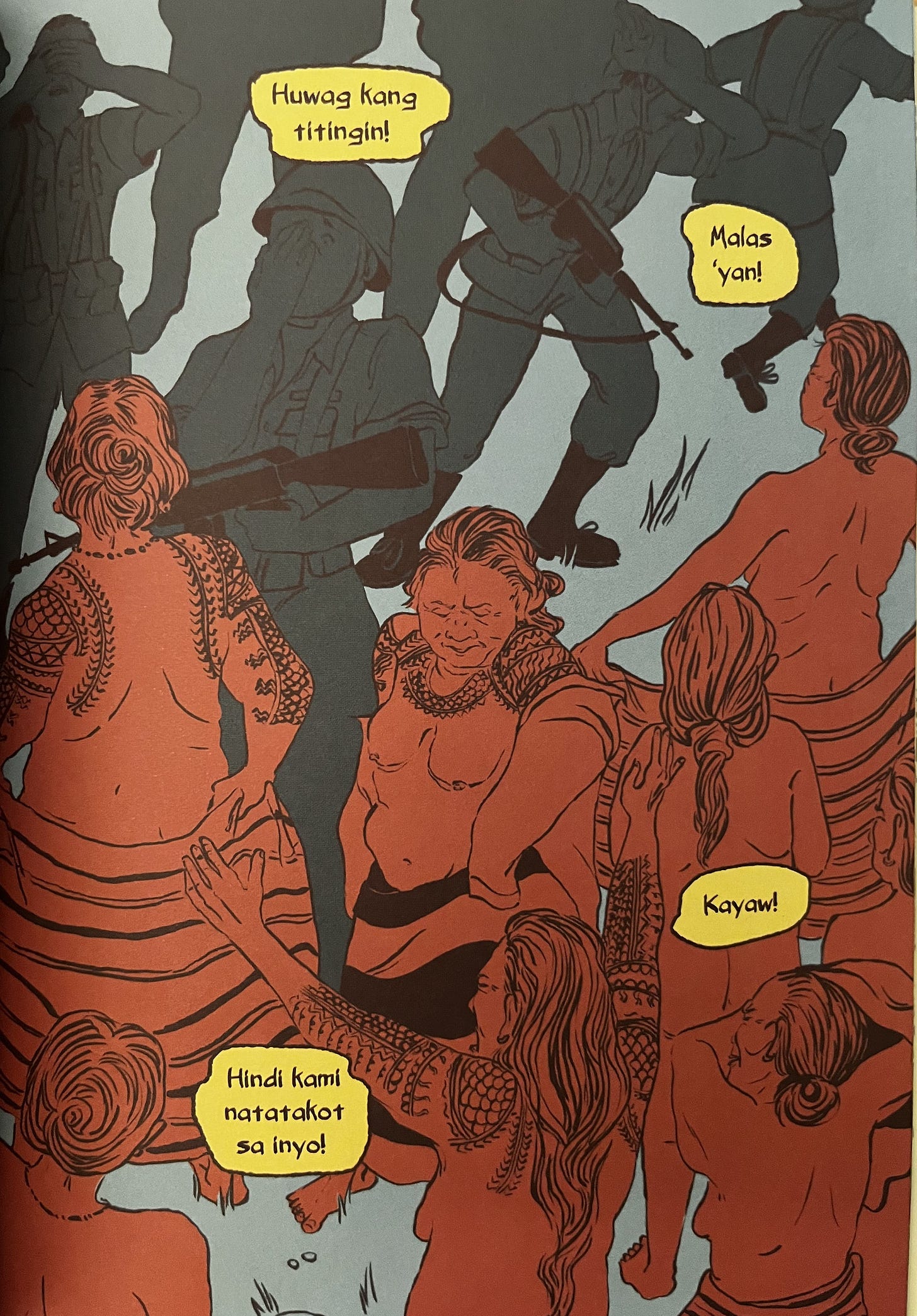

It was the 1970s. The indigenous peoples of the Cordillera had been battling the government to protect their home against what would be a devastating dam in Chico River. One tribe, the Kalinga people, were at the forefront of this battle. If Chico dam were to be built, it would have displaced their tribe and submerged their ancestral land. So they boycotted and protested, and when soldiers came to disperse them, they called every Kalinga woman to go to the river, link arms, and stand their ground in a barricade.

Not one man was present. Only Kalinga women stood by Chico River while the soldiers warned them to leave. Unarmed women, mothers and grandmothers stood guard by the river. The soldiers stepped closer to the barricade, trying to intimidate them, but they all stood their ground. Then, something unplanned happened. Each woman stripped their shirts and bared their chests. Brown and sagging breasts.

“You would hurt us women? You came from a woman,” they said. “Come closer and I’ll crush your balls!”

The soldiers who considered themselves men of God found the sight of wrinkly breasts horrifying. “Jusko po!” They looked away and found all haughty anger drained from them. They became ashamed.

The soldiers left. Peacefully, without any Kalinga people harmed. The same story happened in Bontoc, a different part of the Cordillera, where indigenous women stood once more against a mining project.

This famous story was retold around a table of women activists recently. Carol, who had been a dedicated force in the movement for decades, said this: “The Kalinga people knew if they sent men, the soldiers would see them as threats. Violence would be inevitable. They wanted to protest peacefully, so they sent women.”

Macli’ing Dulag may be remembered as the hero and martyr of the Kalinga, but it was Kalinga women who put their bodies on the line for Chico River that day, a crucial victory in the lifelong triumph of protecting their land and home.

Women have always been at the forefront of resistance work. For indigenous women, resistance is their heritage. Overlooked and erased by history, but there all the same—women animate the resistance.

Around that table, exchanging stories and weaving our collective wisdom, I learned a lot from Carol and her life partner, Cye. I asked them if I could write about our visit.

On a recent trip with friends to La Union, where I was practicing saying yes to the ocean and to life, Carol and Cye invited us to visit their permaculture farm. Nestled in the hills a few dozen kilometers from San Juan beach was the small food forest they’ve tended for thirteen years, the Pitak Project. The farm was named for the Ilocano word for mud, pitak—the combination of soil and water which gives life.

Before Pitak farm, Carol and Cye were what’s called “full-time” (FT) activists, dedicating their lives to advocating for farmers’ and indigenous people’s rights. In the Philippines, FTs live closely with the communities they serve, receiving little pay for their work of fighting for justice. It’s a job that demands physical, mental, and spiritual sacrifice—especially when activists in the Philippines are painted as terrorists by the government. Full-time activists are at higher risk of being murdered or disappeared by the state.

Carol and Cye knew the sacrifices of activism too well. They’ve lost some of their close friends to the violence and impunity of the state years ago. I’m sure it was a difficult decision when Cye and Carol left full-time activism to resist in a different way. A better world was possible—they still believed in this—so in 2013 they pivoted to the Pitak Project.

It’s not easy to change the way you resist. Going from a paradigm of fighting the system to creating within the system can be frightening. Am I abandoning the cause, or will my friends feel abandoned? What if I can’t create something worth it? What if, in the end, it’s still destroyed? One of my close friends is a full-time activist, and I had considered going full-time years ago when I was volunteering with a national climate organization, so I know the dilemma personally.

In our conversation under the fruit trees at Pitak, Cye and Carol talked about the necessity of working within the system. “We have to befriend local government officials,” they said. “Our old friends tease us for it, but we work both in and out of the system.” As educators, they teach permaculture practices to farmers and organizations; as activists, they promote sustainable and regenerative living. They work in between the new world and the old.

In the spectrum of resistance that exists within any progressive movement, there are advocates and then there are stewards of a new world—a better world. One tries to change public opinion by disrupting the status quo, using logic to beat the rhetoric of oppressors, while the other focuses on creating spaces of justice where people can physically experience what is usually only hypothetical. Stewards take the question what if and they grow it.

From what I can see, women are still leading the resistance, but ways of resistance can look vastly different from each other. The struggle is a barricade and the struggle is a food forest nestled in the hills.

More than anything, Cye and Carol’s story reminds me of the importance of beginnings. There are times when we need to embrace uncertainty and lean into the creative, expansive possibilities of our desire for a just world. Cye and Carol created a haven in Pitak that feeds not just themselves but their neighbors, too. With their knowledge in permaculture, they’ve taught countless people about living in harmony with the land. I saw a future for myself there in their farm. Despite climate crisis and the relentless privatization of land for corporate profit, I could see myself living a fulfilling life because of Cye and Carol’s work.

The steel spine for resistance that Kalinga women taught us remains. Just yesterday on January 24th, indigenous people and community elders stood in a barricade against the Dupax del Norte mining project headed by Woggle Mining Corp in Nueva Vizcaya. We must wield both strategies at the same time: we need to fight for our land, and we need to grow something worth fighting for.

Thank you for sharing these stories, Maria! 💜 I’ve learned a lot!

Thank you for sharing this story, Maria! And for all that you do.