For the visionaries, healers, disruptors and space-time baddies

Revolutionary work as experimental, creative and caring

The war to be human and to live a life worth living is waged against a life of waste and absolute expendability — Neferti Tadiar1

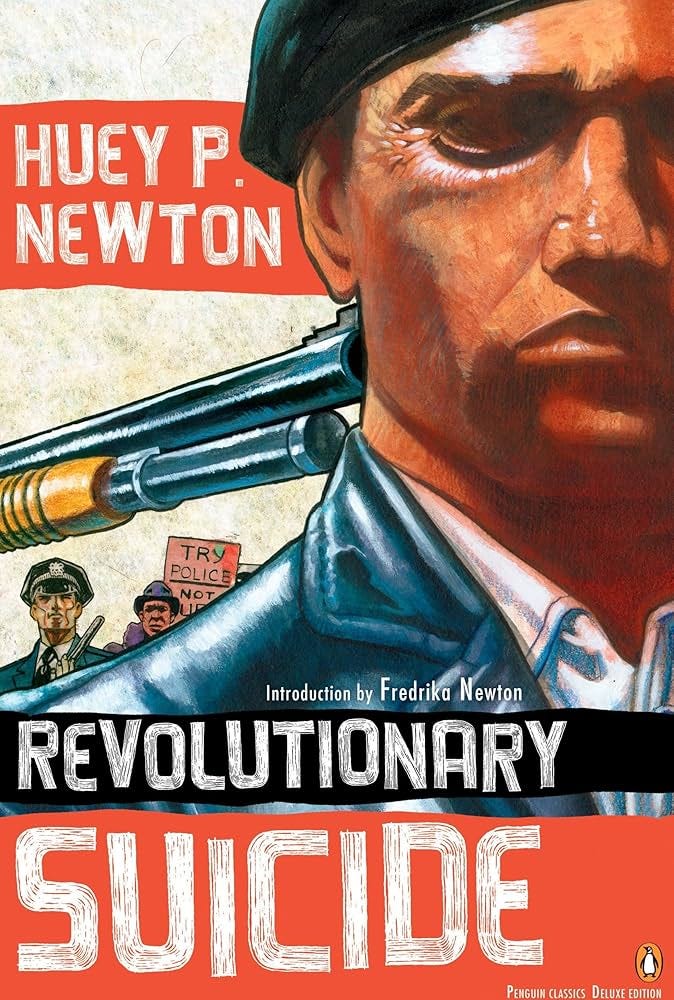

I’m embarrassed to say it. “Revolutionary.” When someone describes themselves as a revolutionary, they are, whether they mean to or not, comparing themselves to the likes of Audre Lorde or Gabriela Silang, Bobby Seale or Huey P. Newton. When someone says “revolutionary,” they claim self-sacrificial values in an age of self-gratification. I just can’t help it. Really? Are you really doing the thing or are you just putting on the aesthetic?

I say all this as one of the least inspiring revolutionaries. I find myself depressed half of the time. I admit to ghosting a few organizations. Mostly, I no longer seek to destroy myself for supposed justice.

“Revolutionary suicide” is the term Huey P. Newton, co-founder of the Black Panther Party, used to describe his central philosophy. It was the title of his autobiography, the book that in many ways radicalized my politics. In his own words, “It is better to oppose the forces that would drive me to self-murder than to endure them.”2 When everyday life is a struggle, you may as well turn that struggle against the Empire. This fiery commitment to the revolution, however, is what would consume him in the end, a dangerous cocktail of paranoia and self-hatred.

It is easy to understand why the concept of revolutionary suicide is problematic. It suggests that you can only find fulfillment through self-sacrifice, whether that’s emotional, spiritual, or material sacrifice. Any other way to live is seen as a waste and even betrayal to the movement. It is the binary of hero or traitor that permeates much of class discourse. This revolutionary work is joyless and impractical—what happens to the world when we have all been martyred? Nothing at all, unless we learn how to live differently.

I no longer seek to destroy myself for supposed justice.

In their book Joyful Militancy, carla bergman and Nick Montgomery write that “undoing Empire also means undoing oneself.”3 We need to become capable of being other than what Empire has taught us. Instead of learning oppression, punishment, and marginalization, we need to learn restoration, care and cooperation, and foster them in turn. In the Panthers, this spirit of care was most alive in their Free Breakfast Programs which fed thousands of children across the country so that kids could properly focus and learn from school. It was a positive strategy of direct action. Instead of, let’s say, lobbying the district for free school breakfasts, the Panthers took matters into their own hands.

The Panthers understood that to get anything done, you have to do it within your community. Do not rely on the state. Capitalism and authoritarianism will not reform itself. It will never prioritize equality over domination. It will continue to promote individualism and competition among us because that is what recreates the system. Focusing on what we can actively create rather than what we need to tear down allows us to take root in Empire’s fissures and grow alternative spaces. As Purvi Shah writes, “We resist collapse by holding space for possibility.”4

This brings me to my understanding of revolutionary work as an experimental, creative and caring practice. In fact, let’s do away with the word revolutionary altogether. This work is for the visionaries, healers, disruptors, worldbuilders, troublers, arcanists and liminal ancestors—those who see the future with the wisdom of the past—space-time baddies. We need everyone. The revolution is not enlisting; the fucking galaxy is.

Theory of Practice (or the Creation Paradox)

What came first: the fascist or the fascist system? I don’t know, but the fascist is surely the chicken in this situation. In seeking to make change, we need an understanding of how change occurs/stirs/comes to be.

Forgive me for using the A word here: According to the anarchist theory of practice, it is our actions which transform both ourselves and the world around us. Actions create change within ourselves as well as change within others and the world. They can either expand or shrink our capacity for care and cooperation, either encourage or discourage practices of care in others.

Reading transforms our beliefs and opinions. Feeding the homeless makes us feel expansive and hopeful. Working in a soul-sucking 9-to-5 trains us to be a laborer.

This theory of practice, that our actions transform ourselves and the world around us, is also the theory of emergence: our small-scale actions, when practiced intentionally, will grow in scale just as fractal patterns emerge from a fern’s leaves.5 If we read regularly, we begin to talk about what we are reading with others. We might lend our books to friends. We might start a book club or a small library. Alternatively, feeding the homeless consistently will over time create organization around that action, bringing more and more people.

When addressing our community needs, we don’t have to make an organization in the sense that it’s recognized by the government, complete with tax-free donations. The organizations that empower people the best are the ones that are suited to our needs, flexible, and based mostly on our resources. There must be no donations from companies or otherwise outsiders looking to improve their social responsibility rating because sooner or later, we would be forced to cater to their needs instead of ours. The more we can build up our resources and invest it in our communities, the stronger our safety nets will be.

The inner work of changing ourselves runs parallel to the work of building community. The two things feed into each other as a positive feedback loop that is in direct opposition to fascist systems based on individualism and domination. As Kropotkin wrote, humans have both the capacity for mutual aid and domination. These can be nurtured; it is up to us which one we choose.

“The War to be Human” p. 7 from Remaindered Life by Neferti X.M. Tadiar (2022).

p. 2 from Revolutionary Suicide by Huey P. Newton (1973). Reprinted with an introduction by Frederika Newton published by Penguin Books, 2009.

p. 31 from Joyful Militancy by carla bergman and Nick Montgomery (2017).

I had the pleasure of being an auditor for Antioch’s MFA Residency, where Purvi Shah spoke about writers resisting collapse and the intersections of storytelling and community. Find out more about her work here.

Emergent Strategy by adrienne maree brown (2017).

*space time baddies* I like that

I love this so much. It really affirmed me. with what I needed to reflect on.