Against co-optation

building stronger networks of solidarity

Dear Reader,

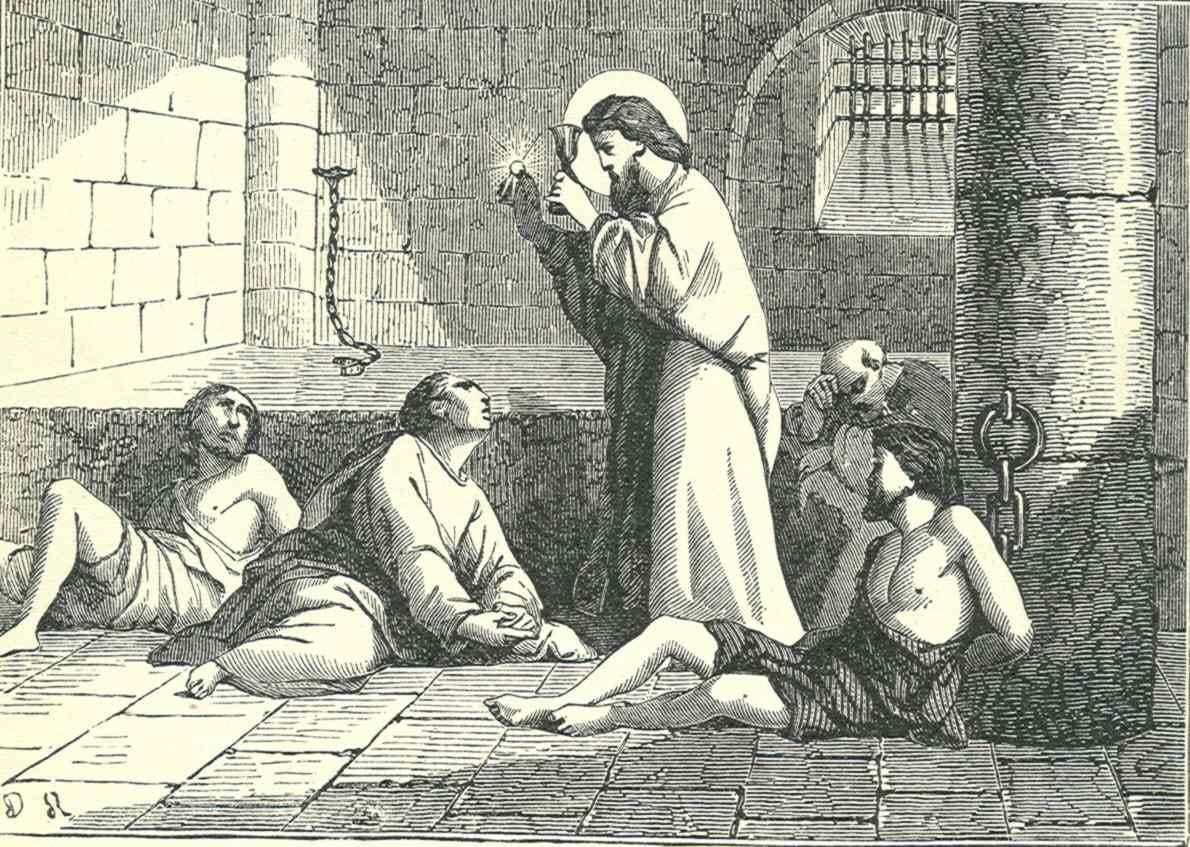

Did you know that the saint whose name we use for the second most commercialized holiday in the world resisted an empire in his lifetime? As the stories go, Valentine was a persecuted Christian priest under the Roman Empire when Claudius II prohibited young soldiers from marrying. The law was enacted so that soldiers’ loyalty would stay with the army and the empire alone, with nothing to distract them from their duty of enforcing and punishing resisters. Valentine not only opposed this decree but facilitated secret marriage rites for young soldiers and their wives. How many couples he blessed, we do not know. He was caught and imprisoned soon after.

It’s ironic that Valentine’s name is associated with bouquets of imported flowers and manufactured heart-shaped chocolates when he was imprisoned for resisting one of the largest hegemonies in history. It echoes the more pernicious irony of invoking a merciful and forgiving god to justify violence and displacement against Palestinian people.

Like Valentine’s story, much of radical culture has been co-opted over the centuries. We should know by now that whatever radical culture we create can and likely will be co-opted and diluted to suit the dominant ideologies. The antidote to this co-optation lies in our discernment of genuine initiatives to dismantle hierarchy and our capacity to build alternative democratic structures where everyone has a seat at the table

Some organizations perpetuate relationships of oppression, whether subtly or overtly. Be mindful of these groups, and listen to your gut when you feel unsafe or unwelcome. For example, militant groups with radical ideologies often fall into the trap of enforcing their ideology in ways that affirm their position of power, as knowledge holders and gatekeepers of capital-T Theory. These organizations are not open to hearing other perspectives and worldviews; they are tunnel-visioned on their way, the right way of radical action.

Theory is helpful in understanding history and our place in it as active political agents. However, it is not the most inviting. It doesn’t facilitate strong relationships built on trust, which is crucial to any resistance movement. Correcting someone’s worldview, as if it were that easy to change someone’s mind, deters people from engaging with a movement. If it’s their first exposure to radical thought, they may hold a negative bias for it and be less likely to engage with similar ideas in the future.

A genuine initiative to dismantle hierarchy must meet people where they are. What are their basic needs that go unmet, like housing, food, or healthcare? Integrate those needs into your goals, and, over time, hold discussions where you explain your worldview, the How and Why those basic needs are unmet. When basic needs are prioritized, people are more likely to listen because they know they’re not just a number in your recruitment quota.

Capitalism’s commodification of everything has eroded our relational skills, but we need relationships to build spaces and institutions that truly serve the people. We need to learn how to be in relationship with each other, even with the people we don’t understand or don’t perfectly align with. Don’t pick your comrades as if picking a life partner, with the expectation of matching perfectly with all aspects of their personality. Pick your comrades based on their capacity to have difficult conversations and adjust accordingly, orienting themselves to your shared goal of liberation. It’s important to be that kind of person, as well.

I think of what Christabel Mintah-Galloway says about relationship-building and liberation: “Relationships aren’t about finding the right people; they’re about becoming the kind of person who can build trust.” If you can have honest, vulnerable conversations that build trust, you’re holding a small pocket of justice for your community.